Notes from the Warehouse Floor

0x41434f

I’ve been thinking a lot about how we train machines to work like people. But nobody talks about what it takes to train people to work like machines. What do we go through? What skills do we have to learn just to do a job that feels invisible to everyone else?

I’m not coming into this with theories or guesses. I’m learning directly from experience. I still work in tech. I still love building things. But recently, I’ve been doing something different. I’m taking jobs that put me inside warehouses and fulfillment centers. I want to see the full picture of how things work when people are under pressure to move, lift, count, and get it all right with barely enough time or support.

I’ve worked in meal kit fulfillment. Now I’m training as a warehouse order selector and also working as an inventory associate. These jobs are not easy. They are physically intense, repetitive, and sometimes dangerous. But they also give me something no textbook ever could: real, lived insight into what breaks, what works, and what could be made better with care, design, and maybe one day, with technology that truly helps.

While building a solution for meal packing errors last year, I realized I couldn't rely on assumptions alone. So I worked as production and quality control ass at a distribution center, and now I'm on the floor again, this time learning how to ride a pallet jack, pick orders, and see where things break. I've been observing everything from scan rate systems to exosuits, turnover to incentives, and how machines are (or aren't) used.

My original idea was a quality control software, but now, I'm interested in safety, turnover, robotics, and automated power equipment. I'm also looking to learn more about how to design warehouse robotics systems that are actually useful. One of my next steps is to find a job working directly with robotics systems like forklifts or cherry pickers. I want to gain first-hand experience to better understand how robotics and AI can augment labor, not replace it.

Week One (April 14 to 20, 2025)

April 14, 2025 - First Day and Orientation

I started training as a warehouse order selector. My schedule runs from 6:00 in the evening to 3:00 in the morning, Monday through Friday for now. In the fifth week, the schedule will change to Sunday through Thursday from 6:00 in the evening till finish.

April 15, 2025 - Starting My Second Job

The next day, I also started working as an inventory associate at a different company. That schedule is Friday nights, 6:00 pm to 6:00 am, and Sundays from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm. I’m still trying to decide which job to keep. Originally, I was more interested in the inventory role (my first inventory assignment is at Petsmart next week). But now, the warehouse order selector job has really captured my attention.

What the Job Descriptions Told Me to Expect

Right after orientation, I started comparing what I was learning to job listings from big companies like Sysco and US Foods. These companies are some of the largest foodservice distributors in the United States.

Here’s what nearly every job description mentioned:

- You must be able to lift 60 to 100 pounds many times in one shift.

- You have to work 8 to 12 hour shifts, often overnight.

- You need to be comfortable using powered equipment like pallet jacks and forklifts.

- You will work in all temperature zones, from freezers to dry storage.

- You might move 2,000 or more cases (boxes) or items in a single night.

- You must know how to use hand scanners and print labels.

- You will walk long distances, bend, twist, and work quickly and accurately.

- Your pay might increase if you are fast, accurate, and make few mistakes.

- Most jobs offer health insurance, 401(k) retirement plans, and paid time off starting on day one.

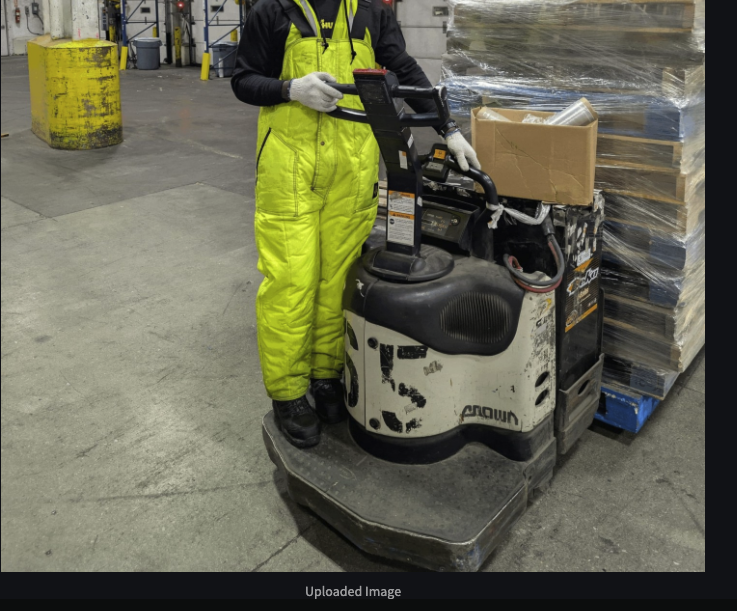

April 16 and 17, 2025 - Learning to Ride the Pallet Jack

We started practicing how to use a front ride pallet jack. It’s like a big powered cart that you ride while steering and picking up pallets loaded with items. At first, we just drove forward and backward. Then we moved on to quick braking.

The hardest part was learning to brake using the throttle, which is the handle you twist to go forward or backward. To stop, you have to shift it quickly in the opposite direction and then return it to the middle. I found it difficult. I was gentle with the handle, trying not to mess up. My trainer told me that was my problem. I needed to trust the machine more and stop overthinking. I also realized that riding the jack felt a lot like riding my bike. You have to focus on where you're going and use your body to guide the movement.

April 17, 2025 - Slotting and Lifting

We learned a task called slotting. That means moving items closer to the edge of the shelves so it's easier to reach them. It helps the team work faster.

I burned about 7,000 calories that night. We lifted a lot. The heaviest thing I picked up was 80 pounds. It was hard, and I definitely felt it.

My trainer noticed that I was stiff and nervous. He asked me to try dancing to relax. He even joked that pallet jack riding takes moves like Michael Jackson or Shakira. I told him I cycle a lot and that I’m used to pushing my body, but I realized he was right. My movements were tense. Once I relaxed, I started doing everything smoothly. That’s when he called me a "smooth operator."

April 18, 2025 - Certification Day

Friday was our big test day. I got certified to operate both the center ride and the front ride pallet jacks. The center ride was easier for me. I learned it in less than 20 minutes. We had to ride through the entire warehouse, taking turns and showing that we could steer safely. I hit one pallet because I turned too sharply, but otherwise, I did well.

With the front ride jack, we had to back up into narrow spaces between pallets to drop off empty ones, just like we’d do at the loading dock. The spaces kept getting tighter. I was still being too careful and slow. My trainer started giving me less time to think, and that helped. He told me to just go ahead and hit the obstacles if I had to, just so I could get rid of the fear. After that, I started doing it right.

We also practiced wrapping pallets and backing up when we couldn’t see what was behind us. You have to lean left or right to peek. That part came naturally once I stopped being afraid of making mistakes.

I asked for extra time next week to keep practicing with the front ride jack. I know what I’m doing, but I’m still being too gentle. My confidence is about a 7 out of 10. I want to be better.

Week Two (April 21 to 27, 2025)

April 21, 2025 – First Day of Week Two

We came in today and signed our certification papers. Then we had the usual huddle, did our stretches, and got on our pallet jacks to ride around the warehouse.

Today was all about getting my confidence up. Last Friday, I rated my confidence with the front ride pallet jack at a 7 out of 10. After today, I feel like I am now at a full 10.

We practiced picking with old orders so we could get used to how to pick items from a batch and properly place them on pallets. To start, I went to the dock area to pick two empty pallets with my front ride pallet jack. After that, I followed my trainer around the warehouse to pick the items for my batch.

I learned how the aisles and racks are numbered. We pick from DA to DJ sections. Each section has shelves numbered 1 through 5. Shelf 1 is the floor, and shelves 2 and 3 are the first and second shelves up. We only pick from floors up to shelf 3. Odd-numbered aisles are on the left side, and even-numbered aisles are on the right side.

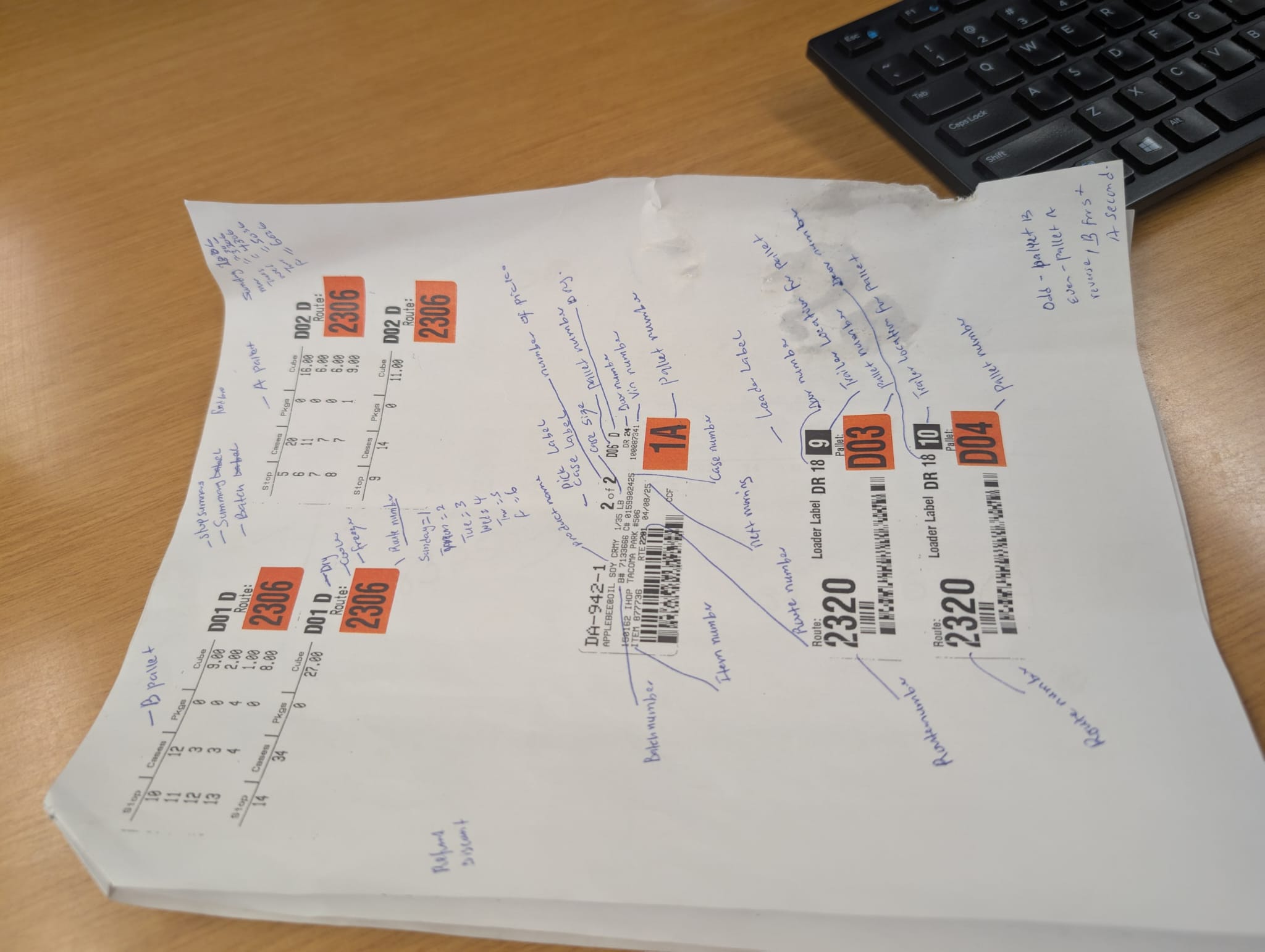

We also have pallet A and pallet B. Pallet A is the inner pallet and pallet B is the outer pallet by the pallet jack battery. This system helps the truck driver load and deliver the pallets in the right stop order to the customers.

We learned that labels must be placed on the side of the pallet, not on the top or bottom, so the drivers can easily scan them. If they cannot scan it quickly, it slows down delivery and could lead to a "short," which means the customer gets refunded or credited for missing items. This costs the company money.

We also practiced arranging the pallets according to the delivery stops. The first stop should be in the easiest spot to grab on the pallet because the trailer will be tightly packed, and the driver needs to unload quickly.

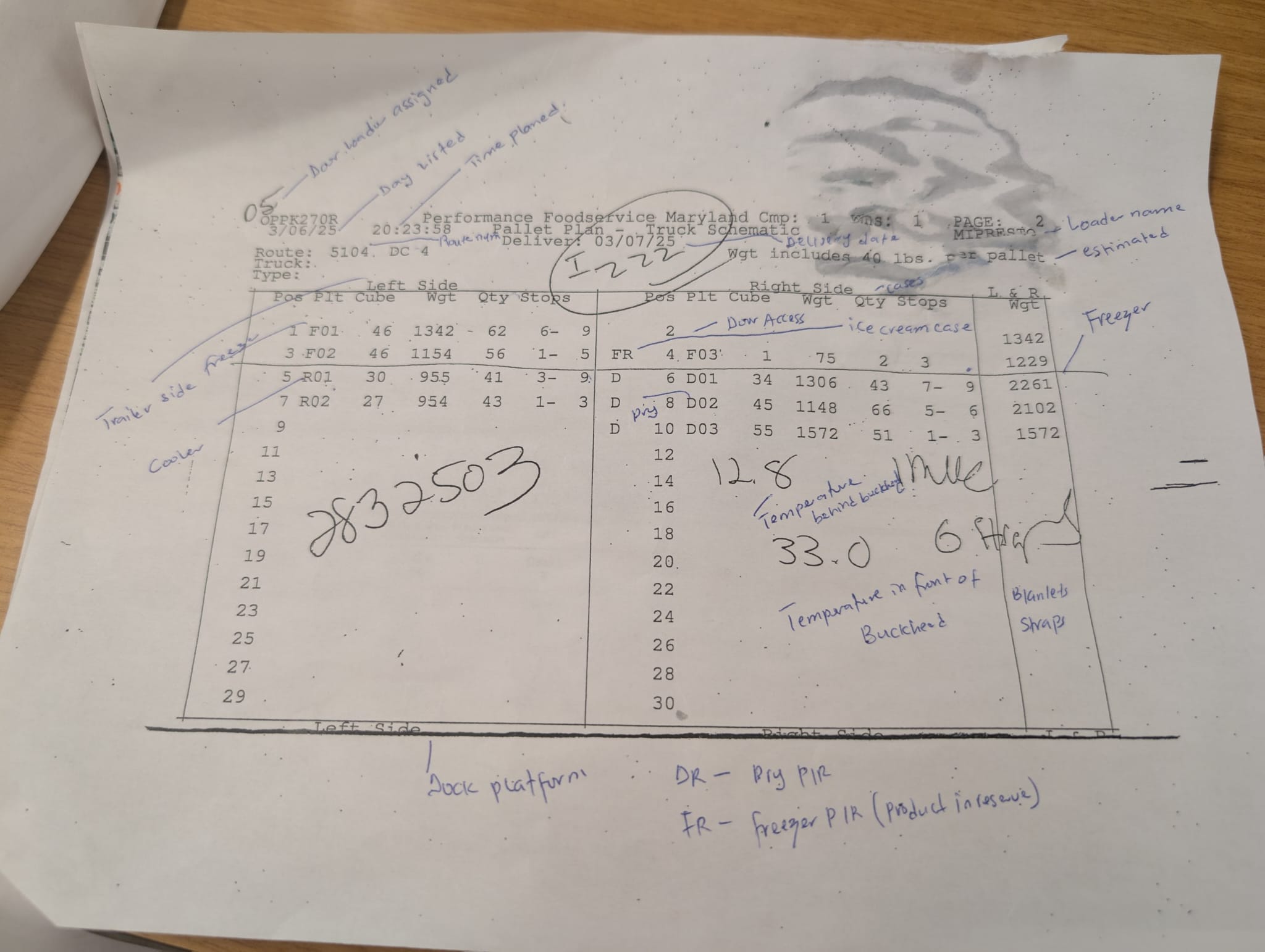

April 22, 2025 – Learning to Read the Labels and Loaders’ Work

We came in and spent the night learning how to read the labels, the loader schematic, and how to use the timesheet tracker that doubles as our productivity and utilization scanner.

We took a written test on it afterward, and I passed it successfully.

Later, we rode around the warehouse and picked up damaged items from the racks, so they could either be repackaged or donated.

From today's training, I really saw how important the loaders are to getting the deliveries right. After order selectors drop the pallets at the dock, the loaders have to check if each pallet is properly tagged and loaded into the trailers in the correct order.

I also learned that if customers do not get their products, the company has to refund them or give discounts. If pallets are overstacked, the loaders have to break them down too.

April 23, 2025 – Lifting Lab and First Real Batch Selection

Today we started with a lifting lab. We watched videos showing the proper and improper ways to lift cases. We learned about using our knees, not our back, lifting within our power zone, and keeping the items close to our body when lifting. Also, instead of twisting our backs to move, we should move our feet.

After the videos, we practiced by moving ten cases from one pallet to another using the right lifting techniques. I followed everything correctly and did not get any complaints or feedback.

After lunch, I did my first real customer batch. It was 250 cases across two stops, which meant two pallets.

At first, I had a little trouble steering the jack when picking up two empty pallets from the dock area, but once I started picking, everything went well.

I made no errors or mistakes. I stacked the items properly onto the correct pallets, made good turns, passed people safely, used my horn often, and made sure the forks were trailing me, just like we were trained.

The only thing I struggled with was stacking perfectly flat. Sometimes I had to move things around to get it even. My trainer suggested using the summary label, which lists the stops and the number of cases per stop, to help plan the stacking better.

I also labeled the pallets correctly on the side. I dropped off the pallets easily at the dock for the loaders.

Overall, it was a really good night. I felt proud because on my first day using a pallet jack last week, I felt unsure if I could even do the job. Now, I can.

April 24, 2025 – First Gig as an Inventory Associate at Sephora

Today, I picked up a shift at my inventory associate job.

Even though the position is supposed to be full-time, I found out that shifts are posted and you have to confirm them within 24 hours. If you do not confirm, the system automatically removes the shift. I have been using this to my advantage by only picking shifts when I am available.

My first shift was at a Sephora store. We had about 30 people there, so we finished the full store count in about two hours.

I worked on Auto Quantity Count, which means scanning each item individually with a scanner. There is also something called Multi Quantity Count, where you scan once and then input the number manually if the items have the same barcode.

One important thing I noticed was about the "Try Me" items. Sephora has a lot of sample or "try me" products placed in front of the real products on the shelves. I almost mistakenly scanned a try-me item, but I noticed it did not have a barcode on it.

That gave me an idea. If I ever build a tool to help with inventory counting, I will train the AI to recognize that unboxed items might be "try me" items. But later, I also saw that some real products were not boxed either, so the AI would have to check for the presence of a barcode and maybe even the location on the shelf to know for sure.

Overall, the job is very much about physical inventory. Scan, count, and avoid batching mistakes.

April 25, 2025 – Ride Along with the Delivery Driver

Today was a different kind of day.

Since there was no warehouse work on Thursday, the trainers sent us out today to ride along with delivery drivers. I was assigned to a 1:30 am route. I arrived early at 1:00 am but had to wait until 2:30 am because my assigned driver called out. Eventually, I rode with a temporary driver.

Our route mostly covered areas close to where I live. I am not sure if that was intentional or random.

Our first stop was a key-in location where we had to open the store and deliver without anyone being there. It was a huge order across dry, refrigerated, and frozen sections. The driver had to break down pallets himself to find everything.

Throughout the ride, I saw firsthand how badly wrong stacking slows down drivers. When stops are not properly separated by zones, the driver has to dig through heavy pallets to find one small case. It wastes time and frustrates the driver.

We even missed delivering one case because it was buried deep inside the pallet and we only found it after we had already passed the customer’s stop. Because of this, the customer will probably get a refund, and the selector will get a mark against their performance.

The driver explained that they do not get paid hourly. They get paid by cases and miles. We had 760 heavy cases that day, including meats, flour, and many heavy items. I helped push and pull 760 cases, totaling 21,667 pounds of weight.

We finished around 4:40 pm after starting at 3:00 am.

I walked 15,009 steps and burned about 4000 calories.

Today was also my first payday from this warehouse job. I used all of it to buy company shares at a 15 percent discount.

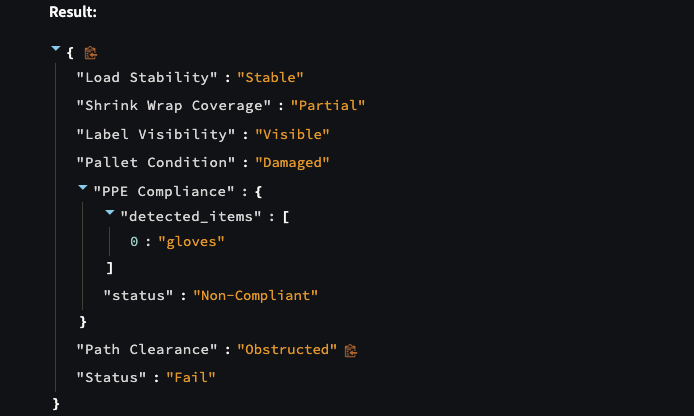

Automated Pallet Analysis Code Demo

Below is a proof of concept Python script I wrote this week. It shows how an AI vision agent could grade a warehouse pallet for safety and compliance. The function reads an image, runs object detection, checks shrink wrap, label position, pallet condition, PPE on workers, and path clearance, then returns a pass or fail report and saves an annotated photo.

import os

import numpy as np

from vision_agent.tools import *

from vision_agent.tools.planner_tools import judge_od_results

from typing import *

from pillow_heif import register_heif_opener

register_heif_opener()

import vision_agent as va

from vision_agent.tools import register_tool

import numpy as np

from vision_agent.tools import load_image, save_image, overlay_bounding_boxes, owlv2_object_detection

def analyze_warehouse_pallet(image_path: str) -> dict:

"""

Analyze a warehouse pallet image for safety and compliance.

This function performs the following checks:

1. Load Stability: Detect if shrink wrap is present to infer stability.

2. Shrink Wrap Coverage: If shrink wrap is detected with higher confidence, mark as 'Complete'.

3. Label Visibility: Check if any 'label' objects are present.

4. Pallet Condition: Check if 'damaged pallet' is detected; otherwise assume 'Good' if a 'pallet' is found.

5. PPE Compliance: Confirm if 'hard hat', 'safety vest', and 'gloves' are all present for a worker.

6. Path Clearance: Check for any 'obstacle' detections.

7. Overall Status: 'Fail' if any major issue is found, otherwise 'Pass'.

A bounding box overlay image is saved to 'annotated_pallet.jpg'.

"""

# 1. Load the image

image = load_image(image_path)

# 2. Run object detection

detections = owlv2_object_detection(

"worker, pallet, forklift, hard hat, safety vest, gloves, shrink wrap, label, obstacle, damaged pallet",

image,

box_threshold=0.1

)

# Helper function to filter detections by label and threshold

def get_detections_by_label(dets, label, threshold=0.2):

return [d for d in dets if d['label'] == label and d['score'] >= threshold]

# 3. Determine each field

# Load Stability & Shrink Wrap Coverage

shrink_wrap_dets = get_detections_by_label(detections, 'shrink wrap', 0.1)

if len(shrink_wrap_dets) > 0:

load_stability = "Stable"

if any(d['score'] >= 0.5 for d in shrink_wrap_dets):

shrink_wrap_coverage = "Complete"

else:

shrink_wrap_coverage = "Partial"

else:

load_stability = "Unstable"

shrink_wrap_coverage = "Missing"

# Label Visibility

label_dets = get_detections_by_label(detections, 'label', 0.2)

label_visibility = "Visible" if len(label_dets) > 0 else "Not Visible"

# Pallet Condition

damaged_pallet_dets = get_detections_by_label(detections, 'damaged pallet', 0.2)

pallet_dets = get_detections_by_label(detections, 'pallet', 0.2)

if len(damaged_pallet_dets) > 0:

pallet_condition = "Damaged"

elif len(pallet_dets) > 0:

pallet_condition = "Good"

else:

pallet_condition = "Unknown"

# PPE Compliance

ppe_items = []

if any(d['label'] == 'hard hat' and d['score'] >= 0.3 for d in detections):

ppe_items.append("hard hat")

if any(d['label'] == 'safety vest' and d['score'] >= 0.3 for d in detections):

ppe_items.append("safety vest")

if any(d['label'] == 'gloves' and d['score'] >= 0.2 for d in detections):

ppe_items.append("gloves")

ppe_status = "Compliant" if len(ppe_items) == 3 else "Non-Compliant"

# Path Clearance

obstacle_dets = get_detections_by_label(detections, 'obstacle', 0.2)

path_clearance = "Obstructed" if len(obstacle_dets) > 0 else "Clear"

# 4. Determine overall status

non_compliant = (

load_stability == "Unstable"

or shrink_wrap_coverage == "Missing"

or pallet_condition == "Damaged"

or ppe_status == "Non-Compliant"

or path_clearance == "Obstructed"

)

overall_status = "Fail" if non_compliant else "Pass"

# Construct the final results dictionary

final_report = {

"Load Stability": load_stability,

"Shrink Wrap Coverage": shrink_wrap_coverage,

"Label Visibility": label_visibility,

"Pallet Condition": pallet_condition,

"PPE Compliance": {

"detected_items": ppe_items,

"status": ppe_status

},

"Path Clearance": path_clearance,

"Status": overall_status

}

# 5. Overlay bounding boxes color-coded by compliance

high_conf_detections = []

for det in detections:

det_color = (0, 255, 0) # Default green

if det['label'] in ['damaged pallet', 'obstacle']:

det_color = (255, 0, 0) # Red for issues

if det['label'] in ['hard hat', 'safety vest', 'gloves']:

if det['score'] < 0.2:

continue

if det['label'] == 'shrink wrap' and det['score'] >= 0.3:

det_color = (0, 255, 0)

if det['score'] >= 0.2:

det_copy = dict(det)

det_copy['color'] = det_color

high_conf_detections.append(det_copy)

annotated_image = overlay_bounding_boxes(image, high_conf_detections)

# 6. Save the annotated image

save_image(annotated_image, "annotated_pallet.jpg")

# 7. Return the dictionary

return final_report

Week 3 Notes (April 28 to May 1, 2025)

April 28, 2025

Today was okay. We started off with huddle, then went straight to picking by taking turns with the other selector assigned to my trainer. We alternated between one batch. For my batches, I got very easy ones. The first batch only had one pallet and 32 cases in one stop, so zoning it was pretty easy. My second batch was just 10 cases in one pallet with one stop. My third batch was 73 cases in 2 stops, also in one pallet. But that batch was 66 cubic, with a lot of big boxes, and I still had to pay attention to 1A 1B even though they were on the same pallet.

I didn't struggle with steering into the pallet to start picking, and I think I'm very comfortable at this job right now like I would be in any engineering job. I knew this because I didn’t get any feedback from my trainer, and I was later told I got complimented on my stacking, safety, and how I didn’t struggle to find the slot. They also liked my positive attitude because I asked a lot of questions and offered to help others.

My utilization time was very good. The estimated time for my first batch was 30 minutes. I finished it in 25. The second batch was estimated for 12 minutes. I completed it in 8. The only one I went 9 minutes over on was the third batch, which was estimated for 40 minutes.

I’m happy because I was fast and accurate. While doing this, I found a lot of interesting things that helped me push the limits of how I’m thinking about building my software. One thing I noticed is you can’t really go wrong if you actually follow the instructions on the scanner. It tells you what slot, what shelf, and even includes the name of the product. If you scan the wrong item, it will not print the label. It only prints when you scan the correct item. So the key is to scan, scan, and scan.

I also learned that safety vests aren't limited to the standard ones. They have hoodies that count as vests because of their colors. That’s an edge case I need to factor into my computer vision model. Not every employee wears a hardhat either. Hardhats are only required for the first 90 days, but people can keep wearing them.

During our huddle, I found out that Sundays are their busiest nights, but also when the most people call out. They usually close between 6 am and 7 am on Monday morning, which makes Mondays tough. To encourage people to show up, they’re offering $100 incentives every week for the next three weeks if you come in on Thursday, Sunday, and Monday and don’t leave early.

Finding a way to fix this is where I see opportunity.

April 29, 2025

The day started slow. Our trainers had their weekly Tuesday meetings and we started late at 6 pm. We began selecting at 9:40 pm. I got a very easy pallet with just 32 cases. Since the group only had 33,000 cases to do, we finished at 1:40 am and went home by 2:00 am. Pretty easy day. Not much selecting.

We also went over our performance from last week. I had zero mispicks, shorts, or safety incidents. My scan rate was 92 percent. It would have been 100, but I had a short slot, which counted against me. A short happens when the item isn’t in the slot, so you have to tap a button on your scanner to alert the forklift operator to replenish it.

I asked them why errors happen. They said it’s either the person who unloaded the inbound truck stacked the wrong item in the slot, or the forklift brought the wrong item. Since selectors are the last line of defense, we’re supposed to scan every item and make sure the name matches the label. But people get move cases around when finding their case on slots, and that’s how wrong products get placed in wrong slots. It’s exactly the kind of human error I saw at the fulfillment center. Some items look almost identical.

April 30, 2025

Today was different. We weren’t supposed to start picking on our own until tomorrow, but a lot of people called out, so they had us do our own batches. I actually enjoyed it. I was riding my jack through every aisle, picking from the slot based on what my scanner told me.

I did 8 batches. Some had one pallet, others two. Stops ranged from 2 to 13. For the first 6 batches, I met the standard time. The last 3 took longer because of the each boxes. Each boxes are items you have to pull individually from a case and place in the each box on the pallet. You can easily mispick here because it’s busy and disorganized. If the item itself doesn’t scan, I scan the slot to find the item name, then look around for the match.

Because I noticed so many errors happen here and they told us the same during training, I suggested they treat each boxes like reserve items and have short runners get them when needed. I burned 6400 calories and took 18,000 steps. I struggled with stacking since I didn’t know the box sizes ahead of time, so I kept restacking. Not wrong, but it eats time.

May 1, 2025

Same as yesterday. I did 8 batches, again between 1 and 2 pallets each. This time, stacking was easier because I had seen most of the boxes already. I also got better at scanning. I now know if a case doesn’t scan, try the slot, or another case. Scanning is the only way to confirm the name and size match.

Even though the night wasn’t as crazy, I went 5 to 10 minutes over on some batches. That’s because the time estimate assumes everything is perfect. In reality, people block aisles, spill cases, forklifts are in the way, or shrink wrap needs to be cut. You might even have to remove empty pallets. All of this adds time.

Another big issue is short picks. If a slot is empty or has less than required, I have to short it. The scanner lets me select how many are short. If the slot gets refilled while I’m still on the batch, I’ll get sent back. If not, the short runner gets it. My software has to handle this too.

I noticed a few edge cases:

Real turnover problem. Six people have quit since I joined. People say the job isn’t bad, but the schedule is unpredictable and a lot of folks have second jobs or kids.

High absences. Some nights we have 20 people call out. That’s why management is always begging folks to stay.

The workload can be heavy. Some nights we pick 60,000 cases.

They’re trying to fix this with incentives. If you show up and work full shifts on Sunday, Monday, and Thursday, you get $100 per week. I think people like the job, but they hate the unpredictability.

From my perspective, the culture is very different from the fulfillment center. People are respected. Management knows your name. Trainers still help on the floor. Mistakes are retrained, not punished.

This makes me think deeply about what I’m building. On one hand, some people are glad that tech like exosuits and automation isn’t here yet. On the other hand, they’re quitting because the work is unsustainable. So what’s the right move?

Is this a misaligned incentive problem, or is it about balancing augmentation with automation? I think the answer is somewhere in between.

And I don’t think self-driving trucks solve it all either. A driver still has to unload. I’ve heard some of them say they’re looking for “no touch freight.” And when pallets aren’t stacked properly, drivers lose time and money, since they’re paid by miles and cases, not hours.

This is exactly why the risk disclosures in SEC filings talk about “the ability to find qualified drivers and warehouse associates.”

Also, about labels. Ideally, labels should face outward, but stacking doesn’t always allow that. Some cases are too small or hidden inside the pallet. I originally thought I could use the stop summary label to track pallet layout, but stacking constraints make that unrealistic.

So my app has to account for all of this. Not just the barcode and product ID, but the stacking reality, the labeling inconsistencies, the short picks, the restacks, and all the ways real work differs from theory.

Finally, I learned that about 50 percent of the current warehouse selectors are under 90 days. They also gave anniversary certificates for 1-year and 3-year staff, plus birthday cards to people celebrating this month. Top performers for scan rate, safety, most replenishments, and loader counts get canteen bucks.

That says something about the culture too.

May 1, 2025 (Continued) – Reflection on Automation, Drivers, and Real-World Edge Cases

I don’t think autonomous electric forklifts and pallet jacks are the answers to most of these problems yet. I say this as someone who rides autonomous vehicle and really likes it, but I’ve noticed areas where it still gets confused. Mostly, it struggles with edge and corner cases that weren’t included in the training data.

For instance, the car is great at adjusting to regular speed limits, bbut I’ve noticed it often misses the posted speed limits in construction zones. Those signs are usually temporary and attached to mobile signboards, so the car keeps going at the regular limit it picked up earlier. It also gets confused when there are no clear markings or when another driver behaves unpredictably.

I told my co-trainee and the driver I rode with last Friday that I’ve gained a newfound respect for truck drivers. That driver was so good I told him directly that most of the maneuvers he pulled off were so flawless my car would have been beeping with forward collision warnings or just flat-out struggling. Two moments stood out.

One was when he took a very wide turn around a tight curb. He came extremely close but never hit it. You might think it’s because the truck rides higher, but as we kept driving, I realized it wasn’t just about height. He just knew exactly what he was doing and could adapt quickly, even in areas he hadn’t been before.

The other moment was him backing into a very tight alley for a delivery. It wasn’t an easy alley to back into. He tried twice and nailed it on the second try. He told me to be the spotter and stop cars if any came, but honestly, I didn’t need to do anything. He did it all himself.

So yes, autonomous forklifts and pallet jacks sound good on paper, but I’m not convinced we have all the pieces yet. Funny enough, one of the pallet jack manufacturers, Crown, actually makes a semi-automated model called the QuickPick Rapid. We have some of those at work, but nobody uses them the way they were designed to be used.

When I mentioned this to my coworkers, they didn’t believe me. Our trainers weren’t even aware. I had to show them a video demo from Crown’s own website to prove it. These features are meant to advance the pallet truck remotely or automate part of the movement, but here we just ride them manually like every other pallet jack.

I even hopped on one myself to make sure. It felt just like a regular one. I’m still trying to figure out why no one is using it the right way. Is it a training issue? A feature lock? Something else? I’ll update this later once I know.

When I first started thinking about how to fix some of the problems I’ve seen, my first idea was, “What if we just build autonomous pallet jacks and forklifts?” But now, after actually working here, I’m not so sure.

It’s not just a question of whether we can build it. It’s whether the machine can adapt fast enough and safely enough in messy, unpredictable, real-world conditions. And even if it can, it might still be too slow or too expensive for most warehouses.

We already have the tech, but it’s not really solving the right problem, at least not yet.

Week 4 Notes (May 5 to May 10, 2025)

May 5, 2025

Today started like every other day. We had 62,800 cases to ship out and got right into selecting. I didn't have any mispicks or shorts from my Thursday selection. The day was generally okay, except that I came in sick. I got sick over the weekend with a blocked nose, heavy sneezing, and a cough. I thought it might have been due to the dust or other particles from the cases we were selecting and stacking. But one of the new selectors told me he had the same issue because we were going from dry to cold areas at the dock to drop off and pick up pallets, then coming back to dry. I also noticed about five people trying to hold off their mucus.

At the huddle, the VP of operations said we shipped out the most cases in the facility’s history yesterday, breaking a record. The last time they came close was a day in December 2024 when they shipped out 60,200 cases. Not only did we ship many cases, but drivers also made 93 trips. By 6 pm, only ten trucks were left on their last stops. Our goal for tonight was 58,800 cases. The VP mentioned this week is the busiest in food distribution because of Mother's Day, so we had many cases to ship out by Thursday. I left late, around 5 am because my last batch had a lot of cases and stops, and still battling my running nose and developing a bad headache towards the end of the shift.

May 6, 2025

Today is our short day. We started at 6 pm and ended at 1:00 am. One thing I noticed is that we finish early on Tuesdays not only because the cases are half of our standard cases, but because they have perfect attendance on Tuesday. For context, we had 32,000 cases today and only one person called out, so we left one hour earlier than last week. We also did our week 1 training quiz today and I aced it.

Aside from that, my trainer did an observation on me. I have a perfect pick rate and scan rate and very good safety observations, but my speed is not on par with my accuracy and safety. So for this week, we are expected to run at 50 percent, and I'm actually running between 56 percent to 65 percent, which isn't a problem. They just wanted to see a 5 percent improvement every week until the 16 weeks of training are complete. By then, we are expected to hit 95 percent.

During the observation, my trainer noticed that most of my time is spent on stacking. I don't necessarily have issues with stacking, the problem is that I'm hesitant with placing the case on the existing stack and just moving on. What I'm actually doing is probably "overthinking" the stacking where I want to make sure that stop 1 and stop 2 are within reach on the front, so I keep readjusting as I go. It’s taking me 6 to 9 minutes for batches with heavy boxes. So they just want me to try and get 1A in the front and not worry about the rest of the stop for now.

But the thing is, I'm actually not just restacking. Since I know I only have to hit 50 percent this week, I’ve been using that time to experiment with how to actually make the zoning better beyond just saying how many cases go into each zone and stop. For instance, one of my batches had a lot of stop 1 zone 1 cases in the same aisle, so it was easy for me to place them on the cases of the existing stacks. Another thing I’ve also learned is that a bunch of waters can serve as a good base, but it also largely depends on how it's stacked and which restaurant it’s going to, because many of them order big boxes that are mostly light and go to zone 2. But I won’t get to zone 2 until DG to DH.

The goal for me right now is to really optimize my base from CH to DF and use all the corners of my pallets. I also learned that not all pallets are the same. Small pallets don’t give you enough real estate, and your jack matters a lot. Some jacks can tilt your cases. I changed my jack today and could feel the difference in case stability. The batch summary really gives you a good idea of how many cases each stop has, but because you can’t tell ahead what types of cases they actually are, you have to adapt as you go.

Again, I’m running the expected numbers, have zero errors, and am very safe. So I’m using this week to learn the pallet mechanics and how sequencing could be done better. I need to figure out all possible scenarios because for my camera to be able to scan a pallet and detect if all items are there, I need to stress-test pallet mechanics and explore all the possible ways of stacking. To them, it might seem like I’m over-indexing on stacking. To me, I’m just identifying edge and corner cases, because getting pallet mechanics right is my software’s bread and butter to catch mispicks and shorts. I’m basically gathering real-world training data for my vision agent.

May 7, 2025

I didn’t go to work today. I was very sick. My head was pounding, I had a severe headache, blocked nose, and kept drifting in and out of sleep. I woke up just ten minutes before my shift was supposed to start. I called out through the attendance line and decided to use the day to catch up on other areas of my life and start sketching out the first draft of the software I’m building.

While working on the design, I kept feeling strongly about not just staying at the application layer, but owning the entire infrastructure stack. Not just the app, but the data layer. These warehouses are sitting on a goldmine of data: scan rates, mispick rates, shorts, safety incidents, picker performance, shift-level throughput. And yet, most of it goes underutilized.

The opportunity isn’t just building dashboards or robot or AI wrapper. It’s building the foundation. Something like Plaid or Scale AI, but for warehouses. Something that holds all the operational context and becomes the substrate on which the rest of the tooling can run. The more I think about it, the more I realize I don’t just want to build an app. I want to train the models. I want to build the sensors. I want to own the operating system of warehouse intelligence.

I also spent time today thinking more about how robotics fits into all of this. A lot of people are betting everything on robots, but I just don’t think that’s where the biggest impact is right now. Robots are flashy, but they come with too many tradeoffs. Cost, speed, integration challenges. I’ve seen the QuickPick Rapid pallet jack sit idle or be used like any other jack because no one knows what it’s capable of or how to use it in their actual workflow. The problem isn’t the machine. The problem is the gap between the machine and the people.

The real opportunity is in better decisions. Smarter systems that help workers make fewer mistakes. AI that handles routine logic, catches errors, and guides people instead of replacing them. The best warehouses in the future won’t be the ones filled with the most machines. They’ll be the ones where the people are the most empowered.

That’s what I want to build.

Earlier today, I was reading about Amazon’s Vulcan robot. It’s a robot with a sense of touch. It knows how much force it’s applying and stops before causing damage. It can pack bins with finesse. It can pick items with precision. That’s impressive, but the part that stood out to me the most wasn’t the tech. It was the emphasis on making things easier and safer for the workers. It’s not about full replacement. It’s about better collaboration.

That thinking is rare. Most companies still chase automation for its own sake, but what I’ve learned over the past few weeks is that the real problems aren’t just about speed. They’re about coordination. They’re about understanding how stacking decisions affect drivers, how poor sequencing delays deliveries, how missed scans ripple through the whole system. It’s about improving the logic behind work.

The more I write, the more I believe in what I’m doing. I don’t have all the answers yet. But I know this: the future of warehouses isn’t just about automating the movement of goods. It’s about automating the thinking behind how work gets done. And if I can get that right, if I can make software that understands pallet mechanics, short picks, and label visibility, I won’t just be building a tool. I’ll be building a foundation.

And one more thing happened today.

I got an email inviting me to the next stage for a robot operator role I applied to last week. This isn’t some random detour. It fits. It’s the natural next step. After weeks of reflecting on how machines do or don’t fit into warehouse work, stepping into robotics feels like the logical extension of what I’ve already been doing. I want to learn where robots fall short, where people compensate, and how we can design better tools that actually match how work gets done.

That moment stuck with me. The technology exists, but it’s not being used right, and that disconnect tells me something important. Robotics can’t just be about performance in ideal scenarios. It has to work with real-world behavior, culture, and incentives. That’s why I want to step into this robot operator role, not because I’m pivoting, but because I’m going deeper.

May 9, 2025

I returned to work after partially recovering. I completed my entire shift and resigned in the morning of May 10, 2025. I resigned to pursue the robot operator opportunity. I thanked them for the time and the opportunity they provided me. They said I could come back anytime. The number of cases for the night was 62,000.

May 16, 2025

I didn’t get the robot operator role after going in for the trial. One of the guys there who I think got the job has a master’s degree in robotics and has built several robots already. He even showed me some of the ones he made, and we exchanged numbers.

What stood out to me the most was how much I learned. I now have a full understanding of how they train their robots and how they generate and prepare the data that powers them. I can’t write publicly about that experience because I signed an NDA, but I walked away with something more valuable than just a job. I left with clearer direction on what I want to build.

Instead of just applying to operate robots, I’m going to build one. I’ve decided to start building a robotic arm that handles warehouse tasks that aren’t time-sensitive, like repositioning pallets from the receiving dock to staging areas for selectors. These jobs don’t require speed. They require precision, reliability, and reduced physical strain on human workers. And that’s where robotics can shine.

Here are a few tasks that my robotic arm could help with:

Pallet Wrapping Tasks Sorting good pallets from bad ones, loading the good ones into a case machine, and keeping the space clear. My robot could be trained to recognize pallet integrity, lift and position pallets, and feed them into machinery.

Pallet Tipping Operations Transferring products from damaged pallets to good ones, removing slip-sheets, and placing loads onto conveyor systems. This is a repeatable, low-speed operation where spatial awareness, tag detection, and smooth motion control are more important than fast response time.

Receiving Dock Repositioning Moving empty pallets from delivery trucks to designated dock zones for further picking or restocking. These transitions happen frequently, but not urgently. The robotic arm could act as a dedicated “pallet handoff” assistant to reduce wait time and allow more consistent flow.

These are the kinds of tasks where a robot doesn’t need to do complex reasoning. It just needs accurate force feedback, a reliable vision system to identify pallet tags and positioning, and compliance with safety zones.

Here are the steps I’m thinking about next:

- Start with ROS or MoveIt to control the robotic arm

- Use a gantry-based setup as a prototype, then evolve into articulated arms

- Integrate a vision module to detect pallet tags and position alignment

- Label old footage I collected from working warehouse shifts using WareSight LabelHub

- Later, build in real-time tracking or even edge-based LLMs for handling simple commands like “move Zone 1 pallets to Conveyor A”

This might be the beginning of something much bigger than just a robot. I’m not just watching the camera feed anymore; I’m building the arm that moves because of it. If I can get this right, I’ll be closer to creating a full embodied AI stack that actually understands work the way people do on the warehouse floor.

Beyond robotics, I’m also thinking about mobile vision AI apps for inventory counting. While drones and robots can help with physical inventory, I see more promise in lightweight, smartphone-based scanning tools. These could empower small store or warehouse associates to scan items quickly by shelf, using auto and multi-scan methods. This approach fits the real conditions I’ve seen on the floor.

Field Interviews as Sustainable Research:

This week, I figured out something important. I can keep learning effectively by just going to warehouse job interviews and asking smart questions. Two recent interviews taught me more than weeks of online research.

At one interview for a vendor compliance auditor role, I learned that I’d be taking structured photos of inbound truck violations and uploading them so they could charge the vendor. The system relies heavily on photographic evidence and real-time uploads.

The second interview was for a warehouse assistant position for a small warehouse that serves Comcast technicians. The warehouse is run by a contractor, and my job would’ve been to:

Keep the place organized, safe, and clean Replenish shelves from pallets Scan equipment in and out per technician Make sure technician IDs are matched correctly when scanning

They do biweekly audits of technician inventory and full monthly inventory counts. The software updates in real time and errors like scanning the wrong tech ID can lead to penalties or write-ups. I was told I’d be the only one in the warehouse most of the time, monitored by camera, and responsible for enforcing safety policies like requiring proper footwear and uniforms.

All of this reinforced what I’ve been thinking: there’s a clear space for tools that enhance visibility, accuracy, and accountability in warehouse environments, without replacing people. I want to build those tools.

What the Securities and Exchange Commission Filings Reveal About Warehouse Work

The filings from companies like Sysco, US Foods, and Performance Food Group with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the agency that requires public companies to share financial and business information, reveal this:

- They all say it’s hard to find and keep warehouse workers and truck drivers.

- Many of their workers quit quickly because of how physically demanding the jobs are.

- They are required to follow federal safety rules, including training and gear to prevent injuries.

- Mistakes like picking the wrong item or missing products from a truck cause serious losses.

- They pay workers more if they work fast and make fewer errors. Some companies offer shift bonuses and safety rewards.

- They must now follow privacy laws that protect employee data, not just customer data.

- These companies are also growing quickly and adding new warehouses, which makes training and safety even harder to manage.

What USDA Data Tells Us About Food Spending

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) tracks food spending across the country. Here’s what they’ve found:

- In 2023, Americans spent more money eating food away from home than buying groceries. The foodservice industry sold about 1.5 trillion dollars worth of food.

- That means nearly 60 percent of all food spending in the United States went to places like restaurants, cafeterias, and hospitals.

- The food industry overall, counting grocery stores and foodservice together reached 2.6 trillion dollars in 2023.

- Most spending in foodservice happens in two places: full-service restaurants and limited-service restaurants (like fast food). Together, they made up nearly 69 percent of the food-away-from-home market.

- People spend more money eating out in the spring and summer. In June and December, sales hit their peaks.

- On average, each person in the United States spent about 3,923 dollars on eating outside the home in 2023. In Washington, D.C., that number was over 10,000 dollars.

- Younger generations, like Millennials and Gen Z, are leading this growth. They want fast service, variety, and technology that makes ordering easy.

This shows how big and fast this industry is growing. But behind all that growth is real physical work. Lifting, walking, driving, organizing, and fixing mistakes. That’s what I’m doing now. And every time I mess up or improve, I learn something about what it takes to build tools that could help.

This isn’t about replacing people. It’s about seeing them. And building from the ground up with that in mind.

That’s why I’m working on a new idea. I want to build something that does for warehouse and foodservice work what some startups are trying to do for office work. But instead of focusing on coding or writing, I’m focused on physical labor. I want to create realistic training environments and simulations that teach machines how to understand the kinds of decisions warehouse workers make every day. Things like picking the right item when there are five similar ones, figuring out what to do when a pallet is blocked, or knowing how to safely bend and lift 80 pounds without injury.

The big companies already collect loads of data, from scanners to video footage. The work is being tracked. But nobody’s using that information to reduce turnover, improve safety, or teach systems how to help workers, not just monitor them.

What I want to build would use this data to help solve the exact problems companies describe in their own financial reports: errors, high turnover, burnout, and injuries. I’m not talking about replacing people. I’m talking about helping them get better tools. Tools that are trained on the reality of their work, not just theory. I’m still early in this journey, but this is where I think the future is. Not in perfecting text responses, but in understanding and supporting the real work that holds the economy together.